You drive me crazy

I just can’t sleep

I’m so excited, I’m in too deep

Whoa oh oh, crazy, but it feels alright

Baby, thinking of you keeps me up all night

– Britney Spears, Crazy (1999)

The Unequal Squeeze

I tell myself I don’t care about the government printing money, because what can I actually do about it? But then someone says the word TRILLION again and I start wondering how many gallons of water I should have before the riots start.

America in 2025 is a strange place. Headlines cheer that inflation is down, meaning prices aren’t rising as fast. They’re still rising. Unless we have deflation, life gets more expensive every month. Framing this as a victory feels absurd when housing, groceries, & medical costs are all materially higher than just a few years ago.

Even accounting for bots and the algorithms, Instagram, TikTok, Reddit, & Twitter provide the rawest economic pulse available. There is wisdom in the comments. Older generations used to dismiss this, but they’re catching on.

A video of someone saying “I make $80k and can’t afford a one-bedroom” resonates because, inconveniently, it’s true. Rent jumps of 30%+ in three years, $16 Chipotle, and stretching credit cards for the basics. You can’t go outside without spending $100. This is mainstream frustration.

When reports say “inflation is under control” but lived reality screams otherwise, people feel gaslit. What we’re hearing isn’t matching what we’re seeing with our own eyes.

Let’s call this situation The Unequal Squeeze. Everyone feels the strain, but not equally.

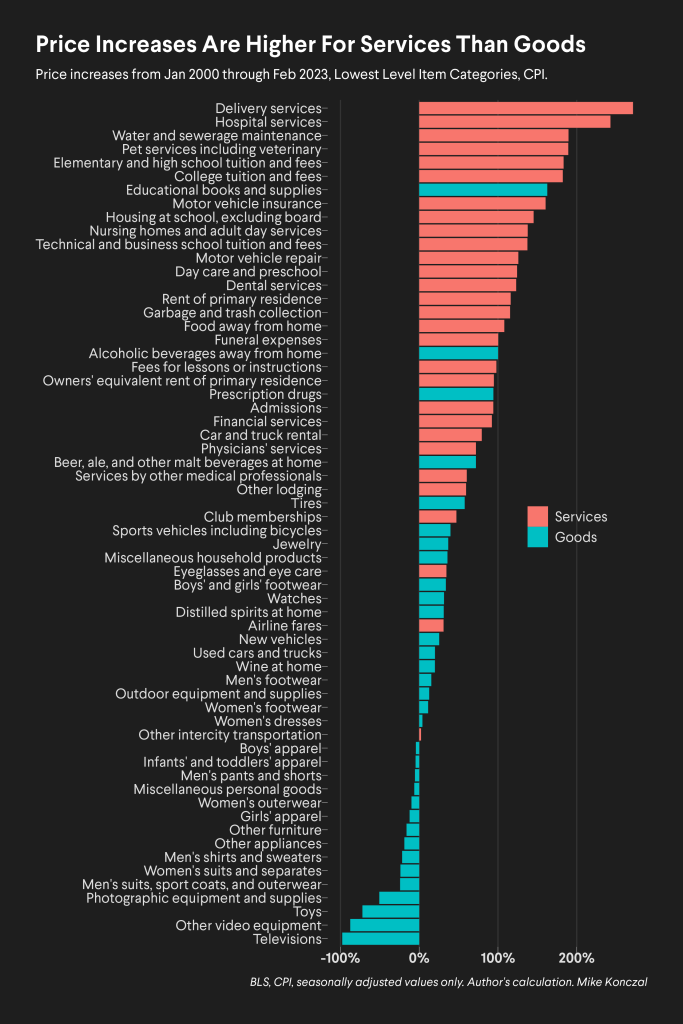

I couldn’t say the government’s inflation number with a straight face. It’s politically too painful to admit how bad it has been. The charitable view is that it’s simply impossible to condense the financial experience of 330 million people into one neat number. Your basket of goods & services is different than my basket of goods & services.

And yet, as the necessities become more punishing, luxuries are becoming relatively cheaper. Trips to Europe used to be rare. Now, you can open up an app and wonder if you’re the only person not in Europe. Most big cities have rooftop bars, farmers markets, trails, parks, and restaurants people 50 years ago could not have imagined.

Housing Friction

Meanwhile, homeowners with 3% mortgages complain about tipping on a $25 cocktail (plus the hidden fee to pay with the QR Code) and text their friends how crazy it is that decent hotels can cost over $800 a night. First world problems are still problems. But they quickly open Zillow and feel better.

Renters and first-time buyers are crushed by housing costs that eat most of their paycheck. Homeowners with cheap loans feel insulated but stuck in their velvet cages. For the wealthy, higher prices mean irritation, for the middle, they’re treading water. For those at the bottom, they mean instability.

Housing is where the Unequal Squeeze shows up most sharply.

Every financial crisis boils down to the same thing: cash isn’t available when it’s expected.

In 2008, millions of homeowners signed up for adjustable-rate mortgages with low payments for the first few years. When the rates reset, the cash wasn’t there to make the higher payment, and forced selling cascaded into a financial meltdown.

This time, most homeowners are locked into ultra-low fixed-rate mortgages (2 – 4% loans) that look almost mythical in hindsight. That opportunity may go down as one of the greatest financial windfalls in American household history. Their payments don’t change. Unless they lose jobs or face major life shocks, there’s little reason for them to sell. That’s why we haven’t seen the type of widespread collapse people have been chirping about.

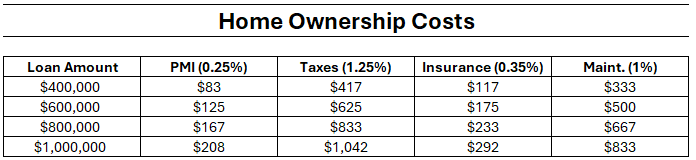

That said, moving to another city or trading up or down would mean giving up a 3% loan for a 7% one, so they stay put. Even those who look secure on paper aren’t relaxed. Stocks are high, housing looks propped up, but it all feels like it’s held together by the TRILLIONS of printed dollars and crossed-fingers. People sense fragility. And, the variable costs keep going up. That keeps the tension balanced across groups.

The divide is not as clean as Haves & Have-Nots. But there is a divide, and it is being felt.

In 1960, the median home cost just over twice median household income.

By 2023, it was more than five times. In major cities, it’s now six to eight. Higher rates compound the pain.

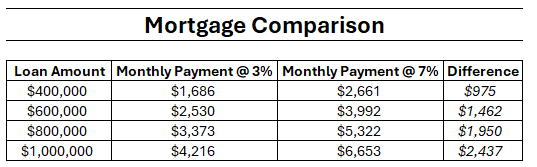

Many buyers think in monthly payments. When a mortgage costs $1,000 more per month than just a few years ago, most families simply can’t stretch.

A house that was expensive-but-possible at 3% interest rates in 2021 is now nearly impossible at 6–7%.

Meanwhile, supply is structurally constrained. One of the main issues in America is zoning because to build, you need people to let you build. Restrictive zoning and permitting policies choke new construction. Homeowners and landlords, whose net worths depend on scarcity, often resist reforms like upzoning. Scarcity becomes policy and they start pulling up the ladder behind them.

Lower interest rates don’t fix this. They simply let buyers borrow more, which pushes prices higher.

To make the point, would you pay $1,000 for a cheeseburger today if someone let you stretch the payments over 30 years?

Boomers tell Gen Z and Millennials that interest rates were high in their day too. Yes, but houses then cost three times income, not eight. Each generation is shaped by many things, but an important one is math.

The truth is, home prices need to come down for many new buyers. But that collides with the reality that existing homeowners want the opposite. Those conflicting incentives create enormous tension between the groups. One generation’s home equity is another’s barrier to entry.

Generational Sentiment

Different groups live in different economic realities.

Financially

- Top 1%: Insulated, view complaints as noise.

- Top 10%: Feel costs, offset with assets.

- Median workers: Wages can’t match costs; debt and side hustles are survival.

- Renters vs Owners: Biggest disparity. Ownership is identity and no one votes for their equity to vanish.

Generationally

- Gen Z: Affordability feels hopeless.

- Millennials: Ownership likely means delayed, luck, or a long commute

- Gen X / Boomers: Confident if already owners, inflation irritating but not existential (some counter-examples like: assisted living/nursing home costs)

Older generations see young people glued to phones and wonder why they aren’t working harder. Younger generations look at the math and see a rigged game. Both have points, but dismiss each other.

Since the pandemic, money itself feels surreal. Pandemic stimulus checks plus $80 billion every time we heard the word Ukraine. You learn someone made a lot of money in a cryptocurrency called PooCoin. Wild swings in pricing on everything from Uber to clothes. People struggle to understand what is going on.

It’s not just economics, it’s psychology. When reality feels like a twilight zone, common sense (“if rent goes from $2,000 to $3,000, fewer people can afford it”) collides with denial (“but people are buying houses, so it must be fine”).

This goes deeper. Many people sense that the difference now is there aren’t many viable exits. The reality is that solving these problems would mean confronting trade-offs nobody wants to face. The government either spends more money to keep the economy going, or it spends less and we have a crash with massive unemployment. And the truth is, only Social Security and military spending are big enough to move the needle. Inflation is the path of least resistance.

That means most “solutions” are hollow, while the real levers are untouchable.

Most people know, deep down, that they aren’t in a position to change those levers. They can adjust their own budgets, grow their skillset, or try to save, but the forces that really shape the economy are out of their hands. That gap between what people can control and what actually drives outcomes explains why denial so often wins out.

Weird Behaviors

Every commercial seems to be a new gambling app. Soap that smells like Sydney Sweeney’s bathwater. Taylor Swift announces a tour date, and half the internet insists it’s a psyop to distract from politics. Nothing is just itself anymore.

The weird part is how the absurd and the serious collapse together. Everything is called a conspiracy while actual corruption is obvious but shrugged off. Nothing is serious, but everything is serious.

The risk isn’t just higher prices. It’s that millions of people are quietly giving up on the idea that the system is fixable at all.

And if something cannot go on forever, it doesn’t just stop. It breaks in ways no one can predict.

Notes